This is an edited, updated version of an essay I wrote in 2008 when this now popular idea was embryonic and ragged. I recently rewrote it to convey the core ideas, minus out-of-date details. This revisited essay appears in Tim Ferriss’ new book, Tools of Titans. I believe the 1,000 True Fans concept will be useful to anyone making things, or making things happen. If you still want to read the much longer original 2008 essay, you can get it after the end of this version. — KK

To be a successful creator you don’t need millions. You don’t need millions of dollars or millions of customers, millions of clients or millions of fans. To make a living as a craftsperson, photographer, musician, designer, author, animator, app maker, entrepreneur, or inventor you need only thousands of true fans.

A true fan is defined as a fan that will buy anything you produce. These diehard fans will drive 200 miles to see you sing; they will buy the hardback and paperback and audible versions of your book; they will purchase your next figurine sight unseen; they will pay for the “best-of” DVD version of your free youtube channel; they will come to your chef’s table once a month. If you have roughly a thousand of true fans like this (also known as super fans), you can make a living — if you are content to make a living but not a fortune.

Here’s how the math works. You need to meet two criteria. First, you have to create enough each year that you can earn, on average, $100 profit from each true fan. That is easier to do in some arts and businesses than others, but it is a good creative challenge in every area because it is always easier and better to give your existing customers more, than it is to find new fans.

Second, you must have a direct relationship with your fans. That is, they must pay you directly. You get to keep all of their support, unlike the small percent of their fees you might get from a music label, publisher, studio, retailer, or other intermediate. If you keep the full $100 of each true fan, then you need only 1,000 of them to earn $100,000 per year. That’s a living for most folks.

A thousand customers is a whole lot more feasible to aim for than a million fans. Millions of paying fans is not a realistic goal to shoot for, especially when you are starting out. But a thousand fans is doable. You might even be able to remember a thousand names. If you added one new true fan per day, it’d only take a few years to gain a thousand.

The number 1,000 is not absolute. Its significance is in its rough order of magnitude — three orders less than a million. The actual number has to be adjusted for each person. If you are able to only earn $50 per year per true fan, then you need 2,000. (Likewise if you can sell $200 per year, you need only 500 true fans.) Or you may need only $75K per year to live on, so you adjust downward. Or if you are a duet, or have a partner, then you need to multiply by 2 to get 2,000 fans. For a team, you need to multiply further. But the good news is that the increase in the size of your true-fan base is geometric and linear in proportion to the size of the team; if you increase the team by 33% you only need to increase your fan base by 33%.

Another way to calculate the support of a true fan, is to aim to get one day’s wages per year from them. Can you excite or please them sufficient to earn one day’s labor? That’s a high bar, but not impossible for 1,000 people world wide.

And of course, not every fan will be super. While the support of a thousand true fans may be sufficient for a living, for every single true fan, you might have two or three regular fans. Think of concentric circles with true fans at the center and a wider circle of regular fans around them. These regular fans may buy your creations occasionally, or may have bought only once. But their ordinary purchases expand your total income. Perhaps they bring in an additional 50%. Still, you want to focus on the super fans because the enthusiasm of true fans can increase the patronage of regular fans. True fans not only are the direct source of your income, but also your chief marketing force for the ordinary fans.

Fans, customers, patrons have been around forever. What’s new here? A couple of things. While direct relationship with customers was the default mode in old times, the benefits of modern retailing meant that most creators in the last century did not have direct contact with consumers. Often even the publishers, studios, labels and manufacturers did not have such crucial information as the name of their customers. For instance, despite being in business for hundreds of years no New York book publisher knew the names of their core and dedicated readers. For previous creators these intermediates (and there was often more than one) meant you need much larger audiences to have a success. With the advent of ubiquitous peer-to-peer communication and payment systems — also known as the web today — everyone has access to excellent tools that allow anyone to sell directly to anyone else in the world. So a creator in Bend, Oregon can sell — and deliver — a song to someone in Katmandu, Nepal as easily as a New York record label (maybe even more easily). This new technology permits creators to maintain relationships, so that the customer can become a fan, and so that the creator keeps the total amount of payment, which reduces the number of fans needed.

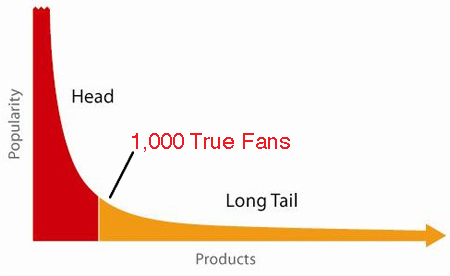

This new ability for the creator to retain the full price is revolutionary, but a second technological innovation amplifies that power further. A fundamental virtue of a peer-to-peer network (like the web) is that the most obscure node is only one click away from the most popular node. In other words the most obscure under-selling book, song, or idea, is only one click away from the best selling book, song or idea. Early in the rise of the web the large aggregators of content and products, such as eBay, Amazon, Netflix, etc, noticed that the total sales of *all* the lowest selling obscure items would equal or in some cases exceed the sales of the few best selling items. Chris Anderson (my successor at Wired) named this effect “The Long Tail,” for the visually graphed shape of the sales distribution curve: a low nearly interminable line of items selling only a few copies per year that form a long “tail” for the abrupt vertical beast of a few bestsellers. But the area of the tail was as big as the head. With that insight, the aggregators had great incentive to encourage audiences to click on the obscure items. They invented recommendation engines and other algorithms to channel attention to the rare creations in the long tail. Even web search companies like Google, Bing, Baidu found it in their interests to reward searchers with the obscure because they could sell ads in the long tail as well. The result was that the most obscure became less obscure.

If you lived in any of the 2 million small towns on Earth you might be the only one in your town to crave death metal music, or get turned on by whispering, or want a left-handed fishing reel. Before the web you’d never be able to satisfy that desire. You’d be alone in your fascination. But now satisfaction is only one click away. Whatever your interests as a creator are, your 1,000 true fans are one click from you. As far as I can tell there is nothing — no product, no idea, no desire — without a fan base on the internet. Every thing made, or thought of, can interest at least one person in a million — it’s a low bar. Yet if even only one out of million people were interested, that’s potentially 7,000 people on the planet. That means that any 1-in-a-million appeal can find 1,000 true fans. The trick is to practically find those fans, or more accurately, to have them find you.

Now here’s the thing; the big corporations, the intermediates, the commercial producers, are all under-equipped and ill suited to connect with these thousand true fans. They are institutionally unable to find and deliver niche audiences and consumers. That means the long tail is wide open to you, the creator. You’ll have your one-in-a-million true fans to yourself. And the tools for connecting keep getting better, including the recent innovations in social media. It has never been easier to gather 1,000 true fans around a creator, and never easier to keep them near.

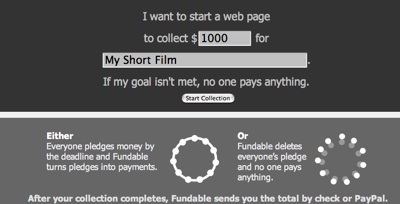

One of the many new innovations serving the true fan creator is crowdfunding. Having your fans finance your next product for them is genius. Win-win all around. There are about 2,000 different crowdfunding platforms worldwide, many of them specializing in specific fields: raising money for science experiments, for bands, or documentaries. Each has its own requirements and a different funding model, in addition to specialized interests. Some platforms require “all or nothing” funding goals, others permit partial funding, some raise money for completed projects, some like Patreon, fund ongoing projects. Patreon supporters might fund a monthly magazine, or a video series, or an artist’s salary. The most famous and largest crowdfunder is Kickstarter, which has raised $2.5 billion for more than 100,000 projects. The average number of supporters for a successful Kickstarter project is 241 funders — far less than a thousand. That means If you have 1,000 true fans you can do a crowdfunding campaign, because by definition a true fan will become a Kickstarter funder. (Although success of your campaign is dependent on what you ask of your fans).

The truth is that cultivating a thousand true fans is time consuming, sometimes nerve racking, and not for everyone. Done well (and why not do it well?) it can become another full-time job. At best it will be a consuming and challenging part-time task that requires ongoing skills. There are many creators who don’t want to deal with fans, and honestly should not. They should just paint, or sew, or make music, and hire someone else to deal with their superfans. If that is you and you add someone to deal with fans, a helper will skew your formula, increasing the number of fans you need, but that might be the best mix. If you go that far, then why not “subcontract” out dealing with fans to the middle people — the labels and studios and publishers and retailers? If they work for you, fine, but remember, in most cases they would be even worse at this than you would.

The mathematics of 1,000 true fans is not a binary choice. You don’t have to go this route to the exclusion of another. Many creators, including myself, will use direct relations with super fans in addition to mainstream intermediaries. I have been published by several big-time New York publishers. I have self-published. And I have used Kickstarter to publish to my true fans. I chose each format depending on the content and my aim. But in every case, cultivating my true fans enriches the route I choose.

The takeaway: 1,000 true fans is an alternative path to success other than stardom. Instead of trying to reach the narrow and unlikely peaks of platinum bestseller hits, blockbusters, and celebrity status, you can aim for direct connection with a thousand true fans. On your way, no matter how many fans you actually succeed in gaining, you’ll be surrounded not by faddish infatuation, but by genuine and true appreciation. It’s a much saner destiny to hope for. And you are much more likely to actually arrive there.

The original 2008 essay follows. It was written before the advent of Kickstarter, Indiegogo and other crowdfunding sites, and includes more the idea’s history. — KK

The long tail is famously good news for two classes of people; a few lucky aggregators, such as Amazon and Netflix, and 6 billion consumers. Of those two, I think consumers earn the greater reward from the wealth hidden in infinite niches.

But the long tail is a decidedly mixed blessing for creators. Individual artists, producers, inventors and makers are overlooked in the equation. The long tail does not raise the sales of creators much, but it does add massive competition and endless downward pressure on prices. Unless artists become a large aggregator of other artist’s works, the long tail offers no path out of the quiet doldrums of minuscule sales.

Other than aim for a blockbuster hit, what can an artist do to escape the long tail?

One solution is to find 1,000 True Fans. While some artists have discovered this path without calling it that, I think it is worth trying to formalize. The gist of 1,000 True Fans can be stated simply:

A creator, such as an artist, musician, photographer, craftsperson, performer, animator, designer, videomaker, or author – in other words, anyone producing works of art – needs to acquire only 1,000 True Fans to make a living.

A True Fan is defined as someone who will purchase anything and everything you produce. They will drive 200 miles to see you sing. They will buy the super deluxe re-issued hi-res box set of your stuff even though they have the low-res version. They have a Google Alert set for your name. They bookmark the eBay page where your out-of-print editions show up. They come to your openings. They have you sign their copies. They buy the t-shirt, and the mug, and the hat. They can’t wait till you issue your next work. They are true fans.

To raise your sales out of the flatline of the long tail you need to connect with your True Fans directly. Another way to state this is, you need to convert a thousand Lesser Fans into a thousand True Fans.

Assume conservatively that your True Fans will each spend one day’s wages per year in support of what you do. That “one-day-wage” is an average, because of course your truest fans will spend a lot more than that. Let’s peg that per diem each True Fan spends at $100 per year. If you have 1,000 fans that sums up to $100,000 per year, which minus some modest expenses, is a living for most folks.

One thousand is a feasible number. You could count to 1,000. If you added one fan a day, it would take only three years. True Fanship is doable. Pleasing a True Fan is pleasurable, and invigorating. It rewards the artist to remain true, to focus on the unique aspects of their work, the qualities that True Fans appreciate.

The key challenge is that you have to maintain direct contact with your 1,000 True Fans. They are giving you their support directly. Maybe they come to your house concerts, or they are buying your DVDs from your website, or they order your prints from Pictopia. As much as possible you retain the full amount of their support. You also benefit from the direct feedback and love.

The technologies of connection and small-time manufacturing make this circle possible. Blogs and RSS feeds trickle out news, and upcoming appearances or new works. Web sites host galleries of your past work, archives of biographical information, and catalogs of paraphernalia. Diskmakers, Blurb, rapid prototyping shops, Myspace, Facebook, and the entire digital domain all conspire to make duplication and dissemination in small quantities fast, cheap and easy. You don’t need a million fans to justify producing something new. A mere one thousand is sufficient.

This small circle of diehard fans, which can provide you with a living, is surrounded by concentric circles of Lesser Fans. These folks will not purchase everything you do, and may not seek out direct contact, but they will buy much of what you produce. The processes you develop to feed your True Fans will also nurture Lesser Fans. As you acquire new True Fans, you can also add many more Lesser Fans. If you keep going, you may indeed end up with millions of fans and reach a hit. I don’t know of any creator who is not interested in having a million fans.

But the point of this strategy is to say that you don’t need a hit to survive. You don’t need to aim for the short head of best-sellerdom to escape the long tail. There is a place in the middle, that is not very far away from the tail, where you can at least make a living. That mid-way haven is called 1,000 True Fans. It is an alternate destination for an artist to aim for.

Young artists starting out in this digitally mediated world have another path other than stardom, a path made possible by the very technology that creates the long tail. Instead of trying to reach the narrow and unlikely peaks of platinum hits, bestseller blockbusters, and celebrity status, they can aim for direct connection with 1,000 True Fans. It’s a much saner destination to hope for. You make a living instead of a fortune. You are surrounded not by fad and fashionable infatuation, but by True Fans. And you are much more likely to actually arrive there.

A few caveats. This formula – one thousand direct True Fans — is crafted for one person, the solo artist. What happens in a duet, or quartet, or movie crew? Obviously, you’ll need more fans. But the additional fans you’ll need are in direct geometric proportion to the increase of your creative group. In other words, if you increase your group size by 33%, you need add only 33% more fans. This linear growth is in contrast to the exponential growth by which many things in the digital domain inflate. I would not be surprised to find that the value of your True Fans network follows the standard network effects rule, and increases as the square of the number of Fans. As your True Fans connect with each other, they will more readily increase their average spending on your works. So while increasing the numbers of artists involved in creation increases the number of True Fans needed, the increase does not explode, but rises gently and in proportion.

A more important caution: Not every artist is cut out, or willing, to be a nurturer of fans. Many musicians just want to play music, or photographers just want to shoot, or painters paint, and they temperamentally don’t want to deal with fans, especially True Fans. For these creatives, they need a mediator, a manager, a handler, an agent, a galleryist — someone to manage their fans. Nonetheless, they can still aim for the same middle destination of 1,000 True Fans. They are just working in a duet.

Third distinction. Direct fans are best. The number of True Fans needed to make a living indirectly inflates fast, but not infinitely. Take blogging as an example. Because fan support for a blogger routes through advertising clicks (except in the occasional tip-jar), more fans are needed for a blogger to make a living. But while this moves the destination towards the left on the long tail curve, it is still far short of blockbuster territory. Same is true in book publishing. When you have corporations involved in taking the majority of the revenue for your work, then it takes many times more True Fans to support you. To the degree an author cultivates direct contact with his/her fans, the smaller the number needed.

Lastly, the actual number may vary depending on the media. Maybe it is 500 True Fans for a painter and 5,000 True Fans for a videomaker. The numbers must surely vary around the world. But in fact the actual number is not critical, because it cannot be determined except by attempting it. Once you are in that mode, the actual number will become evident. That will be the True Fan number that works for you. My formula may be off by an order of magnitude, but even so, its far less than a million.

I’ve been scouring the literature for any references to the True Fan number. Suck.com co-founder Carl Steadman had theory about microcelebrities. By his count, a microcelebrity was someone famous to 1,500 people. So those fifteen hundred would rave about you. As quoted by Danny O’Brien, “One person in every town in Britain likes your dumb online comic. That’s enough to keep you in beers (or T-shirt sales) all year.”

Others call this microcelebrity support micro-patronage, or distributed patronage.

In 1999 John Kelsey and Bruce Schneier published a model for this in First Monday, an online journal. They called it the Street Performer Protocol.

Using the logic of a street performer, the author goes directly to the readers before the book is published; perhaps even before the book is written. The author bypasses the publisher and makes a public statement on the order of: “When I get $100,000 in donations, I will release the next novel in this series.”

Readers can go to the author’s Web site, see how much money has already been donated, and donate money to the cause of getting his novel out. Note that the author doesn’t care who pays to get the next chapter out; nor does he care how many people read the book that didn’t pay for it. He just cares that his $100,000 pot gets filled. When it does, he publishes the next book. In this case “publish” simply means “make available,” not “bind and distribute through bookstores.” The book is made available, free of charge, to everyone: those who paid for it and those who did not.

In 2004 author Lawrence Watt-Evans used this model to publish his newest novel. He asked his True Fans to collectively pay $100 per month. When he got $100 he posted the next chapter of the novel. The entire book was published online for his True Fans, and then later in paper for all his fans. He is now writing a second novel this way. He gets by on an estimated 200 True Fans because he also publishes in the traditional manner — with advances from a publisher supported by thousands of Lesser Fans. Other authors who use fans to directly support their work are Diane Duane, Sharon Lee and Steve Miller, and Don Sakers. Game designer Greg Stolze employed a similar True Fan model to launch two pre-financed games. Fifty of his True Fans contributed seed money for his development costs.

The genius of the True Fan model is that the fans are able to move an artist away from the edges of the long tail to a degree larger than their numbers indicate. They can do this in three ways: by purchasing more per person, by spending directly so the creator keeps more per sale, and by enabling new models of support.

New models of support include micro-patronage. Another model is pre-financing the startup costs. Digital technology enables this fan support to take many shapes. Fundable is a web-based enterprise which allows anyone to raise a fixed amount of money for a project, while reassuring the backers the project will happen. Fundable withholds the money until the full amount is collected. They return the money if the minimum is not reached.

Here’s an example from Fundable’s site;

Amelia, a twenty-year-old classical soprano singer, pre-sold her first CD before entering a recording studio. “If I get $400 in pre-orders, I will be able to afford the rest [of the studio costs],” she told potential contributors. Fundable’s all-or-nothing model ensured that none of her customers would lose money if she fell short of her goal. Amelia sold over $940 in albums.

A thousand dollars won’t keep even a starving artist alive long, but with serious attention, a dedicated artist can do better with their True Fans. Jill Sobule, a musician who has nurtured a sizable following over many years of touring and recording, is doing well relying on her True Fans. Recently she decided to go to her fans to finance the $75,000 professional recording fees she needed for her next album. She has raised close to $50,000 so far. By directly supporting her via their patronage, the fans gain intimacy with their artist. According to the Associated Press:

Contributors can choose a level of pledges ranging from the $10 “unpolished rock,” which earns them a free digital download of her disc when it’s made, to the $10,000 “weapons-grade plutonium level,” where she promises “you get to come and sing on my CD. Don’t worry if you can’t sing – we can fix that on our end.” For a $5,000 contribution, Sobule said she’ll perform a concert in the donor’s house. The lower levels are more popular, where donors can earn things like an advanced copy of the CD, a mention in the liner notes and a T-shirt identifying them as a “junior executive producer” of the CD.

The usual alternative to making a living based on True Fans is poverty. A study as recently as 1995 showed that the accepted price of being an artist was large. Sociologist Ruth Towse surveyed artists in Britian and determined that on average they earned below poverty subsistence levels.

I am suggesting there is a home for creatives in between poverty and stardom. Somewhere lower than stratospheric bestsellerdom, but higher than the obscurity of the long tail. I don’t know the actual true number, but I think a dedicated artist could cultivate 1,000 True Fans, and by their direct support using new technology, make an honest living. I’d love to hear from anyone who might have settled on such a path.

Updates:

One artist who partially relies on True Fans responds with a disclosure of his finances:

The Reality of Depending on True Fans

I have been researching new business models for artists working in the low end of the long tail. How can one make a living in a micro-niche? Is it even possible, particularly in this realm of no-cost copies? I proposed the idea of artists directly cultivating 1000 True Fans, which I wrote up in a previous post. It was a nice thesis that got a lot of blog-attention, but it was short on actual data. I solicited real numbers from those who wrote me, and I also sought out others who had a reputation for thriving on a dedicated fan base, and asked them to share their experiences.

One of the artists I contacted was musician Robert Rich, whom I knew only as a fan (but not a True Fan). Rich was an early pioneer in ambient music, and a force in the Bay Area new age music scene in the early 1980s. He’s prolific, issuing about 40 albums in the past 20 years, many in collaboration with other ambient musicians. Among his earliest albums was “Numena”, which made his reputation, and among his latest is “Eleven Questions”, which was recorded with colleagues in a seven day burst at his home studio.

Robert Rich was one of the first professional musicians to start dealing directly with his fans via his own website, which is why I contacted him. He wrote an extremely candid, insightful and thorough reply to my query. He tempers my enthusiasm for 1000 True Fans with a cautionary realism borne from actually trying the idea. The summary of his experience is so pertinent and detailed that I felt was worth posting in full. With his permission, it follows, slightly edited.

I agree strongly with your basic thesis [of a thousand True Fans], that artists can survive on the cusp of the long tail by nurturing the help of dedicated fans; but perhaps I can modulate your welcome optimism with a light dose of realism, tempered by some personal reflections.

I have operated on a premise similar to yours for almost 30 years now, before the internet made the idea more feasible. I wanted to make the sort of uncompromising quiet introspective music that moved me deeply when I first heard others do it back in the mid ’70’s. Because of the lingering aftermath of the popularization of psychedelic culture, certain memes leaked out from the avant garde into pop culture, and publishers from the old model were willing to try marketing experimental art-forms to the mainstream. Thus, into the mind of a suburban adolescent growing up in Silicon Valley, merged the unlikely combination of European space-music, minimalism, baroque, world music and industrial/punk, most of which received the benefits of worldwide distribution and marketing – even though we all considered it “underground” at the time.

That means, I grew up as a benefactor of the old system, before demographic marketing analysis helped to cripple the spread of radical thought across subcultural boundaries. I realized from this leakage of experimental culture into the mainstream, that I wanted to be an artist like the ones that moved me deeply. I wanted to speak my personal truth, regardless of the cost. I wanted to serve the role of a modern shaman, while embracing the complexities and ironies of our modern world.

When one sets a course like this, one quickly ponders the financial realities of obscurity. I remember telling myself when I was about 15, “If I can move one person deeply, that’s better than entertaining thousands of people but leaving nothing meaningful behind.” That’s the long tail talking. I suppose when you multiply this idea by a thousand, you have your thesis.

I began self-publishing my music in 1981, struggling to get paid from slippery distributors, trying to keep track of all the shops where I had my albums on consignment. I was relieved over the years when a couple small labels showed interest in helping me, and I could avail myself of their infrastructure. I think I benefitted immensely from this exposure, through labels like Hearts of Space and smaller ones in Europe. I feel in retrospect like I snuck in under the collapsing framework of independent distribution, at a time where small companies could cast a medium-sized fishing net, to catch the interest of listeners who would otherwise never have known they liked this type of music.

If it weren’t for that brief window of exposure, I doubt I would have my “1,000 True Fans” and I would probably have kept my day job. If I hadn’t also developed skills in audio engineering and mastering, I would be hungry indeed. If it weren’t for the expansion of the internet and new means of distribution and promotion, I would have given up a long time ago. In this sense, I agree wholeheartedly that new technologies have opened the door for artists like me to survive. But it’s a constant struggle.

The sort of artist who survives at the long tail is the sort who would be happy doing nothing else, who willingly sacrifices security and comfort for the chance to communicate something meaningful, hoping to catch the attention of those few in the world who seek what they also find meaningful. It’s a somewhat solitary existence, a bit like a lighthouse keeper throwing a beam out into the darkness, in faith that this action might help someone unseen.

Now in my mid-forties, I still drive myself around the country for a few months every year or so, playing small concerts that range in audience from 30 to 300 people. I’m my own booking agent, my own manager, my own contract attorney, my own driver, my own roadie. I sleep on people’s couches, or occasionally enjoy the luxuries of Motel 6.

In your article you quote the term “microcelebrities” which rings ironically true to me. I suppose I experience a bit of that, when some of the 600 people whom I see on tour come up to me after a show and tell me that my music is very important to them, that it saved their life, that they can’t imagine why I’m not performing in posh 3,000 seat theaters rather than this art gallery or that planetarium or library.

In reality the life of a “microcelebrity” resembles more the fate of Sisyphus, whose boulder rolls back down the mountain every time he reaches the summit. After every tour I feel exhausted but empowered by the thought that a few people really care a lot about this music. Yet, a few months later all is quiet again and CD/downoad sales slow down again. If I take the time to concentrate for a year on what I hope to be a breakthrough album, that time of silence widens out into a gaping hole and interest seems to fade. When I finally do release something that I feel to be a bold new direction, I manage only to sell it to the same 1,000 True Fans. The boulder sits back at the bottom of the mountain and it’s time to start rolling it up again.

So let’s look a bit at the finances. If I can make about $5-$10 per download or directly sold CD, and I sell 1000, I clear a maximum of $10,000 for that year’s effort. That’s not a living. Let’s say, after 20 concerts I net about $10,000 for three to four months worth of full time effort. That’s not a living.

In my case I’m lucky. I can can augment that paltry income through some of the added benefits of “microcelebrity” including licensing fees for sample clearance and film use rights, sound design libraries, and supplemental income from studio mastering and engineering fees. So, I make about as much money as our local garbage man; and I don’t smell as bad after a day of work. (Note that if copyright laws vanished then much of that trickle of supplemental income would dry up, so you might imagine I have mixed feelings about both sides of the free-information debate.)

Thanks to the internet, I am making more money now, selling directly to 1000 True Fans, than I was during the days on Hearts of Space selling 20,000 – 50,000 copies. But had I not benefitted from the immense promotional effort that it took for HOS to sell those albums, I probably wouldn’t be surviving today as a full time artist.

I have about 600 “true fans” and 2000 seriously following listeners… more on the fringe perhaps. My database has about 3,000 names but I only hear from most of these people every few years. Occasionally someone new shows up and buys everything I ever made. It’s not a simple answer. For example I know I have at least 500+ serious fans in Russia who never paid me for anything, because they get it all as bootlegs. My 4 or 5 “True Fans” in Russia inform me of these things. Many “fans” don’t feel compelled to pay for the art that moves them, or perhaps they cannot pay because of economic circumstances or the inverse laws of convenience.

The number of incoming new “fans” roughly matches attrition, perhaps. I am certainly able to communicate more directly with each individual, but that also means I have less time in the day to actually create new art (half the day doing email is not unusual.) Digital distribution seems to lower perceived value and desirability. Ease of access reduces any sense that it’s special or personal. Compressed audio quality and lack of physical artwork create the sense of a lowering in collectible value. I try hard to counteract these forces with high quality audio and informing listeners about the importance of the source… but people don’t always think about the details.

A further caveat: it’s easy to get trapped into the expectations of these True Fans, and with such a tenuous income stream, an artist risks poverty by pushing too far beyond the boundaries of style or preconceptions. I suppose I have a bit of a reputation for being one of those divergent – perhaps unpredictable – artists, and from that perspective I see a bit of a Catch 22 between ignoring those expectations or pandering to them. If we play to the same 1000 people, and keep doing the same basic thing, eventually the Fans become sated and don’t feel a need to purchase this year’s model, when it’s almost identical to last year’s but in a slightly different shade of black. Yet when the Fans’ Favorite Artist starts pushing past the comfort zone of what made them True Fans to begin with, they are just as likely to move their attention onwards within the box that makes them comfortable. Damned if you do or don’t.

I don’t want to be a tadpole in a shrinking puddle. When the audience is so small, one consequence of specialization is extinction. I’ll try to explain.

Evolutionary biology shows us one metaphor for this trap of stylistic boundaries, in terms of species diversity and inbreeding (ref. E.O. Wilson). When a species sub-population becomes isolated, its traits start to diverge from the larger group to eventually form a new species. Yet under these conditions of isolation, genetic diversity can decrease and the new environmentally specialized species becomes more easily threatened by environmental changes. The larger the population, the less risk it faces of inbreeding. If that population stays connected to the main group of its species, it has the least chance of overspecialization and the most chance for survival in multiple environments.

This metaphor becomes relevant to Artists and True Fans because our culture can get obsessed with ideas of style and demographic. When an artist relies on such intense personal commitmen from such a small population, it’s like an animal that relies solely upon the fruit of one tree to survive. This is a recipe for extinction. Distinctions between demographics resemble mountain ranges set up to divide one population from another. I prefer a world where no barriers exist between audiences as they define themselves and the art they love. I want a world of mutts and cross-polinators. I would feel more comfortable if I thought I had a broader base of people interested in my work, not just preaching to the choir.

Indeed the internet is a tool that allows artists to broaden their audience, and allows individuals in the audience to broaden their tastes, to explore new styles, to seek that which surprises them – if they want surprise, that is. The internet can also give us tools more narrowly to target specific demographics and to strengthen those assumptions that prevent acceptance of new ideas, nudging people towards algorithmically determined tastes or styles. Companies can use demographic models and track people’s search patterns to pander to their initial tastes and to strengthen those tastes, rather than broaden their horizons. This problem doesn’t lie within the technology of the internet, but within the realities of capitalism and human psychology.

Like most technologies, the internet is morally neutral and we can better use its powers to assist the broadening of artistic expression, to assist minority artists to make a better living by communicating directly with their audience, to create tools that help people discover the surprising and iconoclastic, rather than to reinforce only that which supports their existing inclinations. Starving artists will probably remain starving, although perhaps with new tools to dig themselves a humble shelter; and as in the past, some of these artists will use those tools to build sand castles or works of great art.

— Robert Rich

I am deeply grateful to Robert for his generous and courageous disclosure of his real-life finances. Very few of us are willing to do that. But the truth about money is powerful. In the coming days, I will report in summary the real-life True Fan economics that other willing artists have shared with me.

I report the results of my survey of artists supported by True Fans

The Case against 1000 True Fans

My 1000 True Fans post provoked much discussion on other blogs. One blogger mentioned in passing that Brian Austin Whitney had suggested a very similar idea a few years ago. I had not heard Whitney, nor his proposition, and I missed this reference while researching, but I am impressed with how convergent our ideas are. Whitney organized Just Plain Folks, a community for independent artists. Writing on New Year’s Eve 2004, Whitney said,

I have a notion that we’re turning a corner (or experiencing a swing in the pendulum) where an artist who focuses on a smaller number of fans and serves them with a high level of direct interaction and communication will be the new model for success, even in the face of new technology and the shift in old school music business procedures. I think a new definition of success will be the artist who has 5000 passionate fans worldwide who spend 20-30 dollars a year on your creative output.

Four months later, on tax day, blogging musician Scott Andrew picked up Whitney’s notion and expanded on it under the title of 5000 Fans.

Brian pointed out that an artist who has 5000 hardcore fans to give him or her $20 each year — be if from CDs, ticket sales, merchandise, donations, whatever — stands to make $100K per year, more than enough to quit the day job and still have health insurance and a decent car.

Now, 5000 is a big number, but not that big. That’s like, what, one-eighth of an average baseball stadium? And you might not even need that many. Here’s an exercise: take your own salary, pre-taxes, and divide it by 20. If you were to quit your job right now and start living as a full-time musician, poet or author, that’s how many fans you’d need, spending $20 each year to support your art. So, if you’re making $30K yearly, you’d need 1500 paying fans each year to replace your salary. And it gets better if you’re willing to take a pay cut. In Washington state, where I live, a person working for minimum wage would only need around 700 paying fans.

The attraction of 5000 Fans Theory is that the numbers, while still large, are very much attainable. You really don’t need millions of fans across the globe to be a career artist, just a few thousand who actually care. And: the committment to find them.

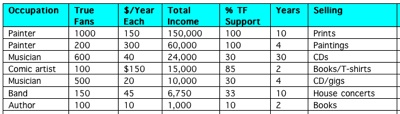

Like Whitney and Andrew, I think there is something important and liberating in seeking a finite attainable number of passionate fans rather than hoping for a rare best-selling career backed by millions of folks who have just heard about you. The problem is that while investigating the data for my thesis, I was unable to find much that could convince me that anyone is actually supporting themselves with 1000 or even 5000 True Fans now. I did get hard financial information from seven creators, in various arts, who are currently supporting themselves in some manner, and to some degree, with True Fans. I got a lot of partial information from about 2 dozen other artists, but these incomplete profiles were difficult to evaluate consistently, so I have not plotted them. The results are displayed in this table:

Going left to right, the chart lists the type of artist, how many True Fans they think they have, how much each fan spends on the artist in a year, the total annual yield of the True Fans, the percentage of their total income the artist estimates this is, the number of years they have been relying on True Fans, and what they actually sell to the fans.

What my research tells me: there are very few artists making their entire living selling directly to True Fans. The few that are, are selling high-priced goods, like paintings, rather than low-priced goods like CDs. But there are many that partially fund their livelihood with direct True Fans. However, most of these artists make it very clear in their notes to me: It takes a lot of time to find, nurture, manage, and service True Fans yourself. And, many artists don’t have the skills or inclination to do so. The fact that very few creators wholly sustain themselves with direct True Fans may be because it is a job few want to do for very long.

True-fan-dom is also certainly not a goal that very many creators have life-long yearnings for, which may be another reason few are doing it. Who dreams of having only 1000 True Fans instead of making a record that goes platinum, or penning a best-seller? Nobody. At least not yet.

But ever the optimist, I am heartened that with some work, it is possible to find partial support from direct True Fans. Micro patronage has always been an option, and indeed a part of, most artist’s livelihood. What is different now is the reach and power of technology, which makes it much easier to match up an artist with the right passionate micro patrons, keep them connected, serve them up created works, get payment from them directly, and nurture their interest and love. In previous generations the hefty transaction costs of doing all this made living off of True Fans impossible in practice. My chart shows that it is now possible in practice, though very few are doing it extensively. I think as role models emerge, as business models shift, and as technology continues to lower the transaction costs, more artists will avail themselves of this path. Time will tell.

Let me leave this topic with one last challenge. This comes from my friend Jaron Lanier, himself a musician (and inventor of virtual reality). Jaron has been researching a similar space as True Fans, and as I have, he is also seeking actual cases of “them that is doing it.” He did not find many claiming to be doing it. In fact Jaron concludes that at this moment, most of those musicians making a living in the new direct-fan environments are musicians who made a name first in the traditional mediums of labels, CDs, contracts, or TV, commercial sponsorship. Jaron is investigating only musicians, and his definition of the type of emerging musician he is looking for goes like this:

The musician’s career is not a legacy of the old system (such as Radiohead). The musician has not merely gotten a lot of exposure, but is earning a living wage. I’ll define a living wage as a predictable income sufficient to raise a child. Finally, most of the musician’s income derives from sources that would still be robust in an “open” world that is highly friendly to massive, unregulated file sharing. These include live performances, paid ads on the musician’s website, merchandising, and paid downloads (like iTunes), but does not include label contracts, movie soundtrack placement, and other revenue streams that rely on old, declining media.

Jaron claims that he has not found a single musician that meets this definition. In other words, he claims that there are no musicians who have risen to a successful livelihood within the new media environment. None. No musician who is succeeding solely on the generatives I outline in Better Than Free. No musician born digital, and making a living in the new media.

I bet Jaron there might be three musicians (or bands) out there who meet his definition, but I did not know who they were.

To prove Jaron wrong, simply submit a candidate in the comments: a musician with no ties to old media models, now making 100% of their living in the open media environment.

If none are offered, I surrender the case to Jaron.