This was originally written by Christopher Janz at http://christophjanz.blogspot.com/2014/10/five-ways-to-build-100-million-business.html

Five ways to build a $100 million business

Some time ago my friend (and co-investor in Clio, Jobber and Unbounce) Boris Wertz wrote a great blog post about “the only 2 ways to build a $100 million business”. I’d like to expand on the topic and suggest that there are five ways to build a $100 million Internet company. This doesn’t mean that I disagree with Boris’ article. I think our views are pretty similar, and for the most part “my” five ways are just a slightly different and more granular look at Boris’ two ways.

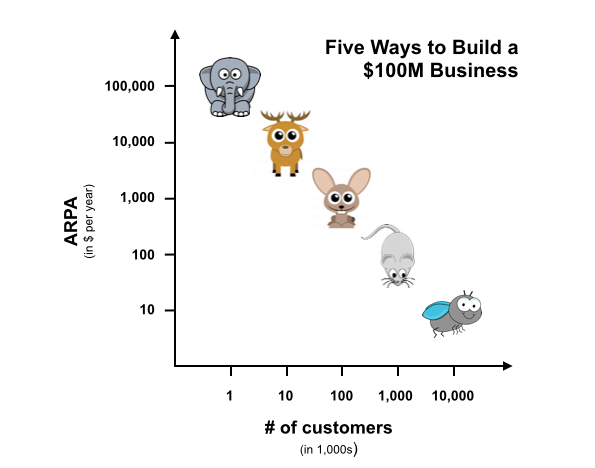

The way I look at it can be nicely illustrated in this way:

The y-axis shows the average revenue per account (ARPA) per year. In the x-axis you can see how many customers you need, for a given ARPA, to get to $100 million in annual revenues. Both axes use a logarithmic scale.

To build a Web company with $100 million in annual revenues*, you essentially need:

- 1,000 enterprise customers paying you $100k+ per year each; or

- 10,000 medium-sized companies paying you $10k+ per year each; or

- 100,000 small businesses paying you $1k+ per year each; or

- 1 million consumers or “prosumers” paying you $100+ per year each (or, in the case of eCommerce businesses, 1M customers generating $100+ in contribution margin** per year each); or

- 10 million active consumers who you monetize at $10+ per year each by selling ads

Salespeople sometimes refer to “elephants”, “deers” and “rabbits” when they talk about the first three categories of customers. To extend the metaphor to the 4th and 5th type of customer, let’s call them “mice” and “flies”. So how can you hunt 1,000 elephants, 10,000 deers, 100,000 rabbits, 1,000,000 mice or 10,000,000 flies? Let’s take a look at it in reverse order.

Hunting flies

In order to get to 10 million active users you need roughly 100 million people who download your app or use your website. This is of course a gross simplification, and the precise number depends on various factors like your conversion rate, how active your users are, churn, etc. But it doesn’t change the take-away: To get to $100 million in ad revenues, you need dozens of millions of users. I know of only two ways to achieve that (plus one mega-outlier which breaks all rules, Google). The first one is to have a product that is inherently social and has a high viral coefficient (Instagram, Snapchat, WhatsApp). The second one is a ton of UGC (user-generated content), which leads to large amounts of SEO traffic and some level of virality. Good examples of this second option include Yelp or our portfolio company Brainly.

Hunting mice

To acquire one million consumers or prosumers who pay you roughly $100 per year, you need to get at least 10-20 million people to try your application. This is – again – a gross simplification, but I believe it’s order-of-magnitude correct. To get to 10-20 million users you almost certainly need some level of virality, too – maybe not Snapchat-like virality, but some social sharing or “powered by”-virality. Great examples of this category include Evernote and MailChimp. If you’re an eCommerce business you might be able to acquire one million customers using paid marketing, but it requires huge amounts of funding.

Hunting rabbits

Most SaaS companies that target small businesses charge something around $50-100 per month, so their ARPA per year is around $1k. To acquire 100,000 of these businesses you need something in the order of 0.5-2 million trial signups, depending on your conversion rate. Let’s assume that your CLTV (customer lifetime value) is $2,700 (assuming an average customer lifetime of three years and a gross margin of 90%) and that you want your CLTV to be 4x your CACs (customer acquisition costs). In that case you can spend $675 to acquire a customer. If your signup-to-paying conversion rate is 10% that means you can spend $67.50 per signup (assuming a no-touch sales model where your CACs can go entirely into lead generation).

So how can you get one million signups for less than $70 each? Most SaaS products aren’t inherently viral, there usually isn’t enough inventory to make paid advertising work at scale, and cold calling usually doesn’t work at this ARPA level. There’s no silver bullet, but the closest thing to a silver bullet is inbound marketing – besides having a fantastic product with a very high NPS (net promoter score) and being obsessively focused on funnel optimization. I’ve written about this in more detail in my “DOs for SaaS startups” series: Create an awesome product, Make your website your best marketing person, Fill the funnel, Build a repeatable sales process. Another option is a an OEM strategy (i.e. getting your product distributed by big partners), which can work but comes with its own challenges.

Interestingly, hunting rabbits looks much less straightforward than hunting flies or hunting elephants. Why we have a strong focus on rabbit hunting SaaS companies nonetheless is something for another post.

Hunting deers

If you’re a deer hunter and want to acquire 10,000 customers paying you $10k per year each, most of the rabbit hunting tactics still apply. An ARPA of $10k per year usually isn’t enough to make traditional enterprise field sales work, and you likely still have to get 100,000 or more leads. The main difference is that when you’re hunting deers you can use an inside sales force to close leads, potentially also to generate leads. It also means that you can pay VARs and channel partners an attractive commission, although I’ve rarely seen this work in SaaS.

SaaS companies sometimes start as rabbit hunters and expand into deer hunting over time. This can work very well and we’re very excited about these types of businesses, but to successfully execute this strategy, SaaS founders with a product/tech/marketing DNA usually have to bring in an experienced VP of Sales who has built an inside sales organization before.

Hunting elephants

Like it or not, most of the biggest SaaS companies derive most of their revenues from selling expensive subscriptions to large enterprises. Workday, Veeva, SuccessFactors, Salesforce.com, you name it. Jason M. Lemkin, another friend and co-investor, once said (I’m quoting from memory) that if you have a good solution for a significant problem experienced by large enterprises, building a $100 million business is relatively straightforward. After all, you only need 1,000 customers, and the $100k you need from each of them is less than they spend on the salary of one executive. I think there’s a lot of truth in that.

The other part of the truth, though, is that it may take you several years and millions of dollars to find out if you really are solving a problem (a.k.a. product/market fit), and once you’re at that point, you still need tens of millions of dollars or more to finance the enterprise sales cycle. This does not at all mean that elephant hunting isn’t attractive. It just requires very different skills, which usually means a founder team with enterprise sales DNA.

* If you have $100 million in annual high-margin revenue, you will likely be able to exit for $500 million to $1 billion or more. That’s the kind of exit most venture capitalists are looking for, although we as a small fund can achieve a great fund performance with somewhat lower outcomes.

** For eCommerce companies, which naturally have a much lower contribution margin than purely digital businesses like SaaS and are therefore valued at much lower revenue multiples, it makes more sense to target $100M in contribution margin.

Update 1

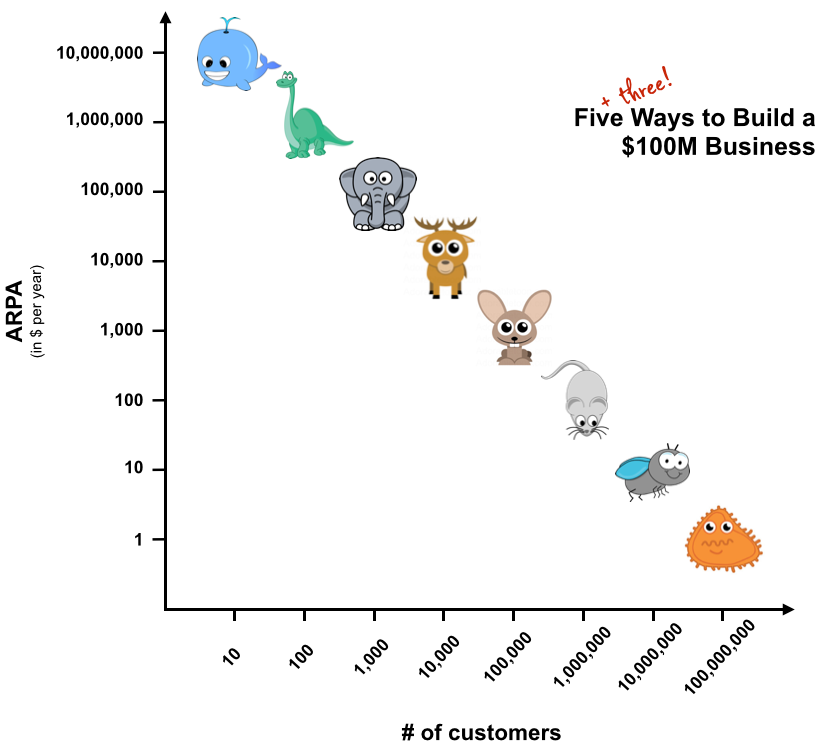

Introducing: the Brontosaurus!

A reader by the name of “Vonsydow” commented that another way to get to $100 million is by having 100 customers, each paying you $1 million per year, and mentioned Veeva as an example. True! Veeva’s ACV is around $780,000. That’s almost an order of magnitude higher than the $100,000 ACV of the “elephants” category, so it’s a different kind of animal. I’d suggest that we call Veeva’s customers Brontosaurus (or Apatosaurus, which seems to be the correct name) but I’m open to other suggestions by people who know more about biology (or paleontology) than me.

Interestingly, it seems like there are only two Brontosaurus hunters in the SaaS world, Veeva and Workday*. What does that mean for SaaS entrepreneurs? Take a look at the backgrounds of the founders of Veeva and the founders of Workday. If your background looks similar – 20+ years of experience selling enterprise software, domain expertise and an extremely strong network in your target industry – get into the Brontosaurus hunting business. If you don’t have a background like this, I think it’s likely that you’re better off starting with smaller animals (but I’d be happy to be proven wrong!).

Whale hunting?

Whale hunting is not the best topic for jokes, but if you know me (who has become a vegetarian a few years ago) you know that I can only mean this figuratively. And the category that I’m going to talk about now just has to be named after the blue whale, the largest animal ever known to have lived on Earth. I’m talking about companies with an ACV of $10 million. If you can sell a SaaS solution at an ARPA of $10 million per year, you need only ten customers and bada-bing, you’ve got a unicorn.

Does that make it easy? Of course not. I’m aware of only one SaaS company which might have an ACV in the neighborhood of $10 million: Palantir, as pointed out by Jindou Lee. In his excellent book “Zero to One”, Peter Thiel writes that Palantir’s “deal sizes range from $1 million to $100 million”. I don’t know if these amounts refer to the price of an annual subscription and I don’t know which part of it is non-SaaS revenue, but it sounds like Palantir’s ACV could be in the $10 million ballpark. Either way, the conclusion along the lines of the conclusion of the Brontosaurus category is: If you’re Peter Thiel, hunt whales. If not, chances are that you should start at a lower end of the market.

Hunting microbes

I’d like to add another species at the other end of the spectrum, too. Jeff Judge pointed out that WhatsApp monetizes its users at about $0.06-$0.07 per active user per year. That means that even if Facebook increases monetization by a factor of ~15 (which I’m sure they can do if they want to) and reaches $1 per active user per year, that’s still an order of magnitude below the $10 per active user per year that I’ve described in the “flies” category, so another category is justified: microbes. If you’re making only $1 per active user per year, you need 100 million active users to build a $100 million business. That means you’ll need hundreds of millions of downloads or signups, which requires an insanely high viral coefficient. If it happens, awesome, but hard to bet on it in advance.

With that, here’s the updated chart, which now shows eight ways to build a $100M business:

The y-axis shows the average revenue per account (ARPA) per year. In the x-axis you can see how many customers you need, for a given ARPA, to get to $100 million in annual revenues. Both axes use a logarithmic scale.

PS: One of my best childhood friends saw my post, and I don’t want to withhold from you what he wrote me: “Mathematically, there are many more ways to build a $100 million business. The easiest one is to start with a $200 million business and lose $100 million”.

________________

* Salesforce.com has a number of Brontosaurus as well as some whale customers. As far as I know, with few exceptions these customers were acquired at a time when Salesforce.com was a $100 million business already. Since this post is focused on ways to build a $100 million business in the first place, I haven’t included Salesforce.com in the Brontosaurus and whale category.

Update 2

Some animals are more equal than others

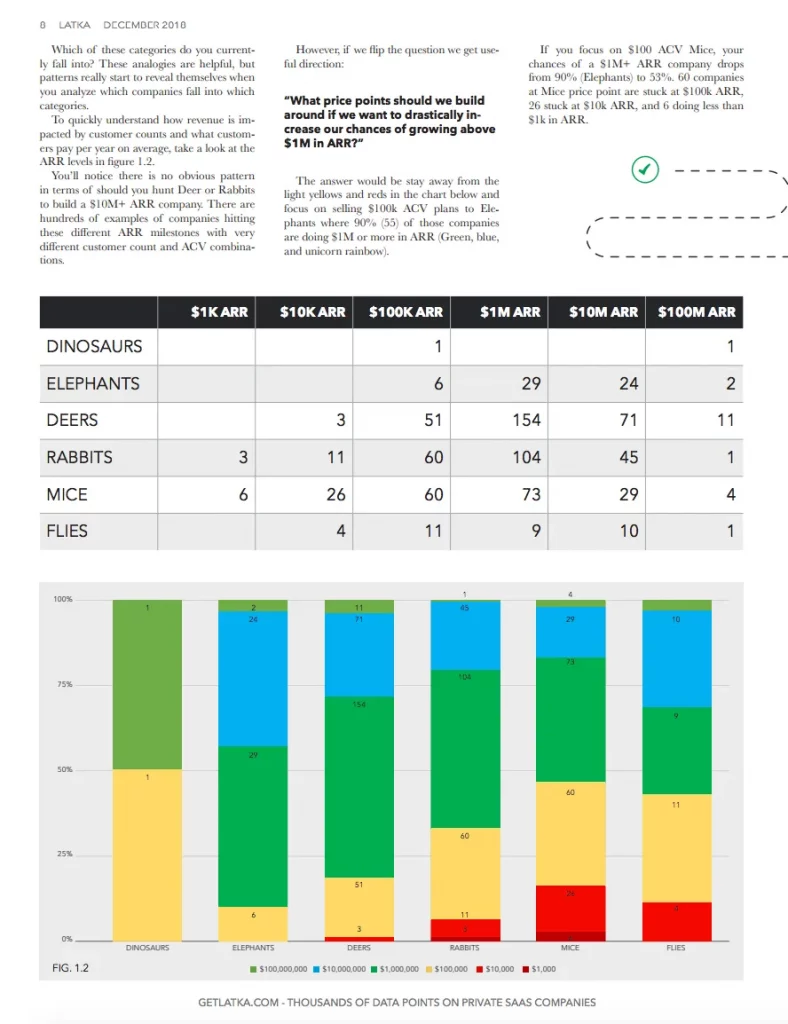

One thing I’ve learned over time is that just because there are five ways to build a $100 million business, it doesn’t mean that those five ways aren’t equally promising. To quote the pigs in George Orwell’s “Animal Farm” (one of the very few books that we had to read at school that I liked): All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.

Let’s take a step back. The key take-away of my “5 animals framework” is very simple: if you want to get to $100 million in annual revenue you’ll have to find customer acquisition channels that are highly scalable and profitable. Otherwise, you’ll never get to the number of customers that you need at your given ARPA. The problem is that most customer acquisition channels are either scalable or profitable but not both at the same time (which is why early CAC/LTV metrics can be so misleading, more about that here). Now, it seems like in some ARPA regions it’s easier to scale profitably than in others. This is certainly what we’ve seen in our portfolio: Several of our SaaS portfolio companies successfully went upmarket — oftentimes from rabbits to deer or even elephants — when they saw that they would hit a growth ceiling in their existing segment. One of the underlying reasons is that in order to get very large, you have to get your churn rate close to zero (or better yet, achieve negative churn), which is usually not possible if you’re selling only to SMBs; the other reason is that outbound sales doesn’t work if your ARPA isn’t large enough, which sort of limits your addressable market to companies that are more or less pro-actively looking for a solution like yours.

If you take a look at this analysis by Sammy Abdullah of Blossom Street Ventures (a VC with the tagline “We’re the anti-VC”, by the way) you’ll see that although Sammy points out that most SaaS companies don’t have an ACV of $50k or more, the vast majority of the 61 publicly traded SaaS companies from his list are deer or elephant hunters. Only 15 of the companies from the list had an ACV of less than $5k at the time of their IPO, and for some of them, the average is misleading because a large part of their revenue comes from customers with a much higher ACV (e.g. Zendesk, Box).

A recent analysis of private SaaS companies by Nathan Latka suggested the same. In his analysis, Nathan looked at 369 companies at around $1M in ARR. 186 of those (50%) are focused on rabbits or smaller animals (he really used those animal analogies). Of the 20 companies with $100M in ARR that Nathan looked at, on the other hand, only 6 (30%) are focused on low ACVs. If you are a successful rabbit-hunting SaaS company and you think you can keep growing in your current segment, these numbers shouldn’t discourage you, though. First, especially the numbers from private companies need to be taken with a grain of salt. And second, even if there is a statistically significant clustering of mid-market and enterprise SaaS companies at the $100M ARR mark, the data also shows that it’s possible to get there with a low ARPA!